What once started with a few hundred producers on sites like Soundclick and MySpace has now evolved into a massive music-licensing industry led by platforms such as BeatStars, Airbit, and Soundee.

Music production has never been easier and today’s resources make it possible for almost anyone to launch a website to sell beats from. Still, beat licensing is serious business.

In this guide, we will explain the concept of beat licensing and particularly focus on the differences between Exclusive and Non-Exclusive Licenses. The information provided in this guide will apply to both artists that are buying beat licenses, and producers selling beat licenses.

Sit back and relax! ☕️ By the end of this guide, you will know everything there is to know about online beat licensing.

Part 1: Beat Licensing Explained

The concept of beat licensing is not hard to understand. A producer makes a beat and uploads it to their beat store. Any artist can buy these beats directly from the store and use them for their songs.

In exchange for their purchase, the producer will provide the artist with a license agreement. A document that grants the artist certain user rights to create and distribute a song.

This license agreement is legal proof that the producer has permitted them to use the beat.

A common misconception is when artists ask producers for free beats. Even when a producer agrees and sends the artist a free beat. The truth is, that free beat is useless as there is no legal proof and permission to use it. This is where the license agreement comes in.

Before we go any further, we have to let go of the common phrases of “buying beats” and “selling beats”. The product that we’re dealing with here is simply not the beat itself. It is the license agreement.

Non-Exclusive Beat Licensing

Non-exclusive licensing, also known as ‘leasing’, is the most common form of beat licensing. For anywhere between $20-300, you can buy a non-exclusive license agreement and release a song on iTunes, Spotify, or Apple Music, create a music video for YouTube, and make money from it! 💰

These are also the types of licenses that are directly available from the producer’s beat store. In other words, you don’t have to inquire for them and you can instantly buy a license from the online store.

In most cases, a license agreement is auto-generated, including the buyer’s name, address, a timestamp (Effective Date), user rights, and the information of the producer.

With a non-exclusive license, the producer grants the artist permission to use the beat to create a song of their own and distribute it online. The producer will still retain copyright ownership (more about this later) and the artist has to adhere to the rights granted in the agreement.

The Limitations of Non-Exclusive Licenses

Most non-exclusive licenses have a limitation on sales, plays, streams or views. For example, the license might only allow a maximum number of 50,000 streams on Spotify and/or 100,000 views on YouTube.

A non-exclusive license also has an expiration date. Meaning that it’s only going to be valid for a set period of time. This could be anywhere between 1-10 years. After the contract period is due, the buyer has to renew the license. In other words, buy a new one.

The license will also need to be renewed as soon as the buyer reached the maximum amount of streams and/or plays. Even if that’s before the contract’s expiration date (!)

Since these licenses are non-exclusive, a single beat can be licensed to an unlimited number of different artists. This means that several artists could be using the same beat for a different song under similar license terms.

Whether this is a problem depends entirely on what stage the artist is in. A beginner artist would be best off with a non-exclusive license, while a signed artist or an artist that is on the verge of blowing up might be better off with an exclusive license.

The different types of Non-Exclusive Licenses

Most producers offer different non-exclusive licensing options. In my case, I offer an MP3, WAV, Premium, and Unlimited License.

Every option comes with its unique user rights. These user rights are often displayed in licensing tables, similar to this.

The more expensive the license, the more user rights you’re getting. These more expensive licenses also come with better quality audio files.

In my case, the second-highest tier, the Premium license, is the most popular. That’s simply because you get the best audio quality, tracked-out files of the beat, and good user rights.

Artists who believe these rights still aren’t sufficient for their song, usually go for the highest tier. The Unlimited license. Or even better, an Exclusive license.

Exclusive Beat Licensing

When you own the Exclusive Rights to a beat, there are no limitations on user rights. Meaning that an artist can exploit the song to the fullest.

There is no maximum number of streams, plays, sales, or downloads nor is there an expiration date on the contract.

The song may also be used in numerous different projects. Singles, albums, music videos, etc. In comparison to non-exclusive licenses, which are usually limited for use in a single project only.

In the case of buying the exclusive rights to a beat that was previously (non-exclusively) licensed to other artists, the artist that purchased the exclusive rights is typically the last person to purchase it. After a beat is sold exclusively, the producer is no longer allowed to sell or license the beat to others.

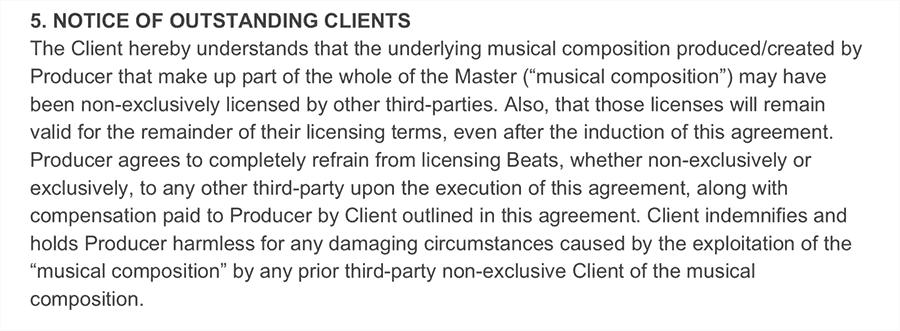

That doesn’t mean the previous non-exclusive licensees will be affected by this. Every exclusive contract should have a section with a “notice of outstanding clients” included.

This section protects these previous licensees from getting a strike by the exclusive buyer.

These are the main differences between non-exclusive licenses and exclusive licenses. But it goes further than that and there’s often confusion around the topics of rights and royalties.

Going forward in this guide, we will go more in-depth about Royalties, Publishing, and Copyright.

Two very different ways of selling Exclusive Rights

For many years, producers had different ways of selling exclusive rights. Luckily, in more recent years, contracts are becoming more streamlined and matching the industry standard.

Still, I want to address two very different ways of selling exclusive rights.

Selling exclusive rights

Selling exclusive ownership

By selling exclusive rights, the producer remains the original author of the music. And is still able to collect writers' share and publishing rights. (again, more about this later)

By selling exclusive ownership, the producer sells the beat including all interest, authorship, copyright, etc. These deals are also known as ‘work-for-hire’. The artist retains actual ownership over the beat and will–from that point on–be considered as the legal author of the beat.

Within the beat licensing industry, selling exclusive ownership is wrong, unethical, and–in most cases–not compliant with Copyright Law.

It’s only right to come to an agreement where both the artist and producer are credited for their work; Legally, financially and commercially.

Part 2: Everything you need to know about Royalties, Writers Share, and Publishing Rights

This is the part that most people struggle to understand. Mainly, because there are lots of different deal structures in the music industry. No worries! 😉 By the end of this guide, you’ll know everything you need to know.

Let’s break things down step-by-step and solely in regards to online beat licensing.

Before we jump into this next section, we need to get a better understanding of two types of royalties first.

Mechanical Royalties

Performance Royalties

Mechanical Royalties

Mechanical royalties are generated when music is physically or digitally reproduced or distributed. This applies to hard copy sales, digital sales (e.g. iTunes), and streams (e.g. Spotify).

Performance Royalties

Performance royalties are generated when a song is performed publicly. This applies to when music is played on the radio, performed live or streamed for example.

Who gets the Mechanical Royalties?

In most cases, the artist is allowed to keep 100% of the mechanical royalties in exchange for the price they pay for the license. Regardless of whether the license is non-exclusive or exclusive.

These days, distribution services like TuneCore, CDBaby, or DistroKid pay these mechanical royalties directly to the artist. That is if the artist works independently

When an artist is signed to a label, the label usually collects the mechanical royalties and might choose to pay (a percentage of) it to the artist.

Advances against Mechanical Royalties in Exclusive Agreements

I intentionally said that “in most cases” the artist gets to collect 100% of the mechanical rights because this does not always apply. There’s an exception to this, which only applies to exclusive rights.

Some producers (including myself) ask for a tiny percentage of the Mechanical Royalties in their exclusive agreements. This could be anywhere between 1-10%.

This is also known as ‘points’ or ‘producer royalties’.

In this scenario, the price an artist pays for the exclusive rights is considered an “advance against mechanical royalties” that might become due in the future. It will be calculated over the Net Profit of a song. Meaning that all costs to create the song, including the exclusive price may be deducted first before the producer gets his cut.

Here’s an example to show you how this could potentially play out in a real-life situation.

Let’s say a producer sells the exclusive rights to a beat for $1,000 as an advance against royalties. His mechanical royalty rate is set to 3%.

The artist paid:

$1,000 for exclusive rights

$500 for studio time

$500 for getting the song mixed and mastered

Total expenses = $2,000

After 1 year, the song generated $10,000 in Mechanical Royalties!

The Net Profit: $10,000 - $2,000 expenses = $8,000 💰

The Producer’s Cut: 3% of $8,000 = $240

As an independent artist, $8,000 is a lot of money to generate on Mechanical Royalties. Still, only $240 has to be paid to the producer.

Why an Advance against Royalties?

It seems pointless, however, there’s a reason why some producers (including me) prefer selling exclusive rights with an advance against royalties.

A few years back, I could easily sell exclusive rights for anywhere between $2,000 - $10,000. (The Good Ol’ Days! 🤠)

These days, it’s considered ‘normal’ to sell exclusive rights for less than $1,000. With all the competition and the beat market becoming more saturated, the prices have dropped and it has become harder to close 4 or 5-figure exclusive deals.

But what if the song blows up!?

What if a song starts generating millions of dollars and you sold the exclusive rights to that beat for less than $1,000?

That doesn’t sound like a fair deal, does it?

An advance against royalties can offer the solution. It’s insurance for the producer just in case the song blows up. It’s also something the artist only has to worry about as soon as the song starts generating serious revenue. And even still, it’s only 3%. 🤷🏻♂️

Who collects the Performance Royalties?

Performance royalties are collected and paid out by Performing Rights Organisations (PROs), such as ASCAP or BMI in the US or PRS in the UK.

(Every country has its organization, check which one is yours)

These royalties are divided into two parts:

Songwriter Royalties (A.k.a. Writer’s Share)

Publishing Royalties

The PROs collect both of these royalties and divide them into two groups.

For every $1 earned on Performance Royalties:

$0.50 goes to Songwriter Royalties

$0.50 goes to Publishing Royalties.

The $0.50 Songwriter Royalties will be paid out to the songwriters directly by the PRO.

The other $0.50 publishing royalties will be paid out to a publishing company or publishing administrator. (more about this later).

What are songwriter royalties?

First, let’s break down the Songwriter Royalties.

The songwriter royalties, also known as the ‘Writer’s share’ will always be paid out to the credited songwriters. This is the part that can not be sold through an exclusive license, other than a work-for-hire agreement.

As I said before, this is wrong in the industry of licensing beats online.

In case you’re getting confused; In copyright law, a producer is considered a ‘songwriter’ too. 🤓

Songwriter royalties apply to anyone who has creative input in a song. Producers, songwriters (lyricists), and sometimes even engineers.

Generally, non-exclusive beat licenses are sold with 50% publishing and writers share. This is usually not negotiable since the music part is the producers’ contribution to your song and is considered half of the song. The lyrics are considered the other half.

It doesn’t matter if there happen to be multiple songwriters that contributed to the lyrics. In that case, this 50% should be divided between them.

Example Non-Exclusive beat licenses:

50% Producer

25% Writer 1

25% Writer 2

As part of an exclusive rights deal, a different split between all creators could be negotiated. It all depends on the price and flexibility of the producer.

While I generally stick to my 50%, some producers sometimes agree to the following example split.

Example Exclusive Licenses:

30% Producer

35% Writer 1

35% Writer 2

What are Publishing Royalties?

Unlike Songwriter royalties, Publishing can be assigned to outside entities called publishing companies. Most independent artist and producers will most likely not have a publishing deal, which means they’ll have to collect the publishing royalties themselves.

Surprisingly, a lot of money is left on the table here. If you’re an independent artist or producer who is only signed up with a PRO and not with a Publishing Administrator, half of what you’ve earned is still waiting for you to collect.

In terms of licensing beats online–regardless of an exclusive or non-exclusive license–the percentage of publishing rights is generally the equivalent of the writer's share.

50% of writers' share equals 50% publishing share.

Part 3: The Copyright Situation...Who owns what?

This is a tricky topic and it goes way further than I can explain here. If you want to know the ins and outs concerning copyright, I suggest you dive deeper into Copyright Law using our good friend Google or consulting an actual attorney.

Again, going forward, I’ll explain about copyright solely in regards to licensing beats online. We’re going to dismantle a song to its creators and copyright holders, hopefully making it clear to you who owns what.

Performing Arts Copyright (PA-Copyright)

Let’s say you’re an artist and you went to search for beats on YouTube. You find one that you like and you head over to the producer's website. You buy a license for that beat, write lyrics, create a song and distribute it through CDBaby, TuneCore or DistroKid.

That song contains two copyrighted elements:

The Music

The Lyrics

The producer owns the copyright to the music and you own the copyright to the lyrics.

Regardless of whether you’ve bought an Exclusive License or Non-Exclusive license. The producer will always own the copyright to the music and the artist will always own the copyright to the lyrics (unless it’s written by someone else other than the artist).

This is what we call Performing Arts Copyright (PA-Copyright).

On a side note: Many believe that you have to register the music or the lyrics with the U.S. Copyright Office yet, in fact, the instant you write something on paper, make a beat in your DAW, or save a demo song to your hard drive, it’s copyrighted!

Sure, there are benefits to properly registering with the U.S. Copyright Office but, failure to do so doesn’t mean you will lose ownership over your creation.

Sound Recording Copyright (SR-Copyright)

Back to that song you made. Together with the producer, you’ve created a new song. In legal terms, this is often referred to as the “Master” or “Sound Recording”.

Now, this is where things can confuse because the difference between an Exclusive or Non-Exclusive license plays a huge role here.

As an artist, buying beats from a producer:

If you have exclusively licensed a beat, you do own the master and sound recording rights.

If you have non-exclusively licensed a beat, you do not own the master and sound recording rights.

In an exclusive license, the Master rights will be transferred to the client (artist) and it will become their sole property, free from any claims from the Producer.

The only exception here is the producer’s right to jointly claim the copyright of the so-called ‘underlying musical composition’. This is what we referred to earlier as the PA-Copyright. The producer is and always will be the original creator of the music.

With a non-exclusive license, the client does not own the master or sound recording rights in the song. They’ve been licensed the right to use the beat and to commercially exploit the song based on the terms and conditions of the non-exclusive agreement. Yet again, they do own the PA Copyright of the lyrics.

Instead, what they’ve created is called a Derivative Work.

What’s a Derivative Work?

In regards to beat licensing, a derivative work is a combination of an original copyrighted work (the beat) in combination with someone else's original work (the lyrics).

Derivative works are very common in the music industry and you probably come across them on a daily basis.

Examples are:

Remixes

Translations (A Spanish version of an English song)

Parodies

Movies based on books (Harry Potter)

These are all so-called ‘new versions’, created using preexisting copyrighted material.

In terms of beat licensing, a non-exclusive agreement authorizes an artist to create such a ‘new version’, using the producer's copyrighted material.

The only person that is able to authorize a derivative work is the owner of the underlying composition itself. In this case, the producer.

When someone licenses a beat on a non-exclusive basis, they’re specifically given the right to create a Derivative Work.

Beats that contain third-party samples

Pretty straightforward up till now, right? Well, I need you to pay close attention now because this is where things often go wrong…

A common misconception when producers are selling beats with samples is thinking they can turn the responsibility of ‘clearing the sample’ over to the artists that license the beat.

I guess somewhere, sometime, someone made a statement about this which is… Entirely FALSE!

This is make-believe and it couldn’t be more wrong! 🤦🏻♂️

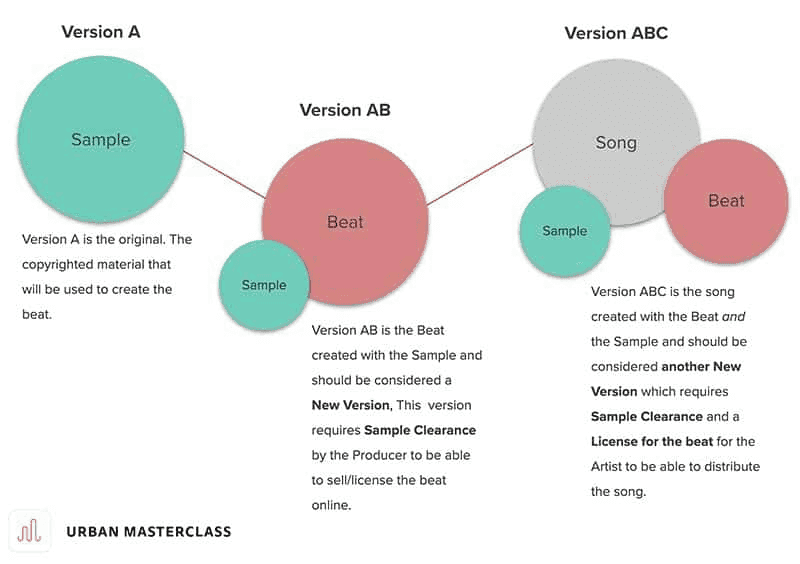

Please view the image below for context…

In the image above, there are two different versions derived from the original sample. (Version AB and Version ABC)

Since both these versions are considered New Work and both contain that original sample–Clearance for Version AB does not account for Version ABC.

Both the Producer and the Artist are required to clear the first sample! Because in this scenario, there are 3 different copyright owners to a song.

Everything falls and stands with clearing the original sample.

This is going to get hard as soon as multiple artists license the same beat and create their songs with it. After a while, there could be a whole lot of Versions ABC deriving from it.

Exactly why I stay away from using samples… 😊

Exclusive or Non-Exclusive, what is best for you?

By now, we’ve covered all the differences between non-exclusive and exclusive licenses. But, if you’re an artist, you might still wonder which option is the best for you.

Besides the difference in price–in every way–an exclusive license is the better option. No doubt! 💯

However, this is not a necessity for everyone. Most artists are better off with a non-exclusive license.

Let’s have an honest view of your current situation…

How many followers and fans do you have?

How many songs have you released to date?

What is the number of plays/streams you get on average? (all platforms combined)

How big is your marketing budget?

Are you getting financial support from a label or publisher?

Ask yourself; What would be the best option for the artist you are TODAY?

You see, most artists are simply not ready to buy exclusive rights yet. And there’s no shame in that at all.

if you’re a young artist working on a mixtape or first album to get your name out there. Why would you spend that much money on exclusive rights if you’re not even sure if the record is going to get big?

The wise(r) investment would be to get one of the higher-tier non-exclusive licenses. Preferably, the Unlimited Licenses.

This allows you to spend less, buy more licenses, release more music, and gradually build your fanbase until you’re ready to take that next step.

A summary of the differences between Exclusive and Non-Exclusive Licenses

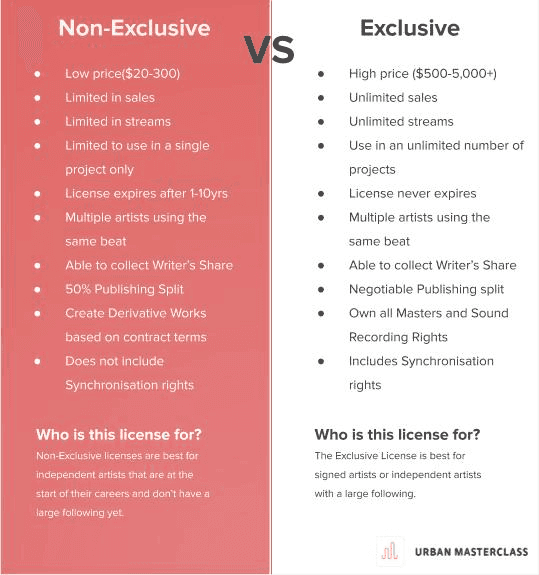

In the image below you’ll find a summary and comparison between Non-Exclusive and Exclusive Beat Licensing. Please note that the Non-Exclusive ‘Sales’ and ‘Streams’ limit does not apply to the “Unlimited” licenses.

Part 4: FAQ About Beat Licensing

We continue to update this guide to provide the answers to the most frequently asked questions concerning beat licensing.

I want to license a beat that is already sold by the producer. Can I reach out to the exclusive purchaser so they can sell me a license?

No, that’s not an option. A common mistake made by artists that are (desperately) trying to license an already sold beat is, thinking they can locate the buyer and buy it from them.

Every exclusive contract states that the beat cannot be resold or licensed to a third party in its original form if it’s not overlayed with lyrics. If they would, that would be a breach of the exclusive agreement.

Someone wants to buy a beat I already sold and asks if I can create a similar one. Can I?

In this case, we’ll have to define the word ‘similar’. If that means re-using parts of the sold beat or replicating melodies you used in that beat, then NO. You’re basically ‘sampling’ a beat that you’ve already sold. In a way, you’re creating a derivative work that you’re no longer allowed to do.

But if that means using a similar song structure. Or similar instruments, yet different chords and melodies, then YES. It’s possible to do that.

I recently bought a non-exclusive license for a beat. Now someone else bought it exclusively. What happens to my song?

Nothing! :) Your license will be in effect for the length of the agreement or until you’ve reached the maximum number of streams and/or plays. (Check your license agreement)

Your non-exclusive license agreement should include an “Effective Date” (the day you bought the license) and an “Expiration Date” (This could also be a period after which your license will expire. E.g. 5 years).

Within the Exclusive contract with the buyer, a so-called “notice of outstanding clients” will protect you from the exclusive buyer to strike you.

My non-exclusive license is reaching its streaming limit but I can’t buy a new license because the beat is already sold exclusively. Do I have to take the song down now?

If your non-exclusive license is reaching its streaming limits and extending the license is not an option, then yes––legally, you will have to take the song down. How unfortunate that might be.

This is the exact reason why the Unlimited Licenses are such a great option, considering they have no streaming cap. All though it’s more expensive, it does avoid (awkward) situations like these.

Someone released a song with one of my beats but didn’t get a license? What’s the best course of action?

Unfortunately, this happens a lot if you’re a producer promoting beats online. Luckily, there are different ways to go about this. The first step is to reach out to the artist(s) and notify them about the unauthorized use of the beat.

Then, offer them 2 options.

Either buy a license so they can keep the song online

Or remove the song entirely from all platforms it’s published on

In the best-case scenario, they adhere to your request. But what if they don’t?

In that case, you have two options.

Leave it be

File for a DMCA takedown (click the link for more info)

If the song isn’t gaining numbers and is of very poor quality (which is usually the case when beats are used unauthorized), it might be best to leave it be. It’s not worth your time and money.

The alternative, filing for a DMCA takedown will cost you some money. I would only consider this if the song is gaining serious numbers (1000s of views or streams on any platform).

I created a beat with another producer. How do we split the publishing and songwriters share?

Collaboration splits are very common these days, yet there’s no quick answer to this question. It all depends on what terms you’re collaborating on.

If you’re collaborating with a producer and you upload that beat to your beat store, the most common split would be 50/50. That goes for sales, publishing, and songwriter share.

When the beat is sold or licensed to an artist, they’re usually granted 50% of the publishing and writers share the song they make. The exact numbers might be different as it depends on the contract terms the producer offers.

But in this case, the split would be as follows.

Producer 1: 25%

Producer 2: 25%

Artist: 50%

Copyright - HEATE

This article, authored by Robin Wesley, is used under license and with permission according to the PRODUCR agreement.